Layers of Meaning

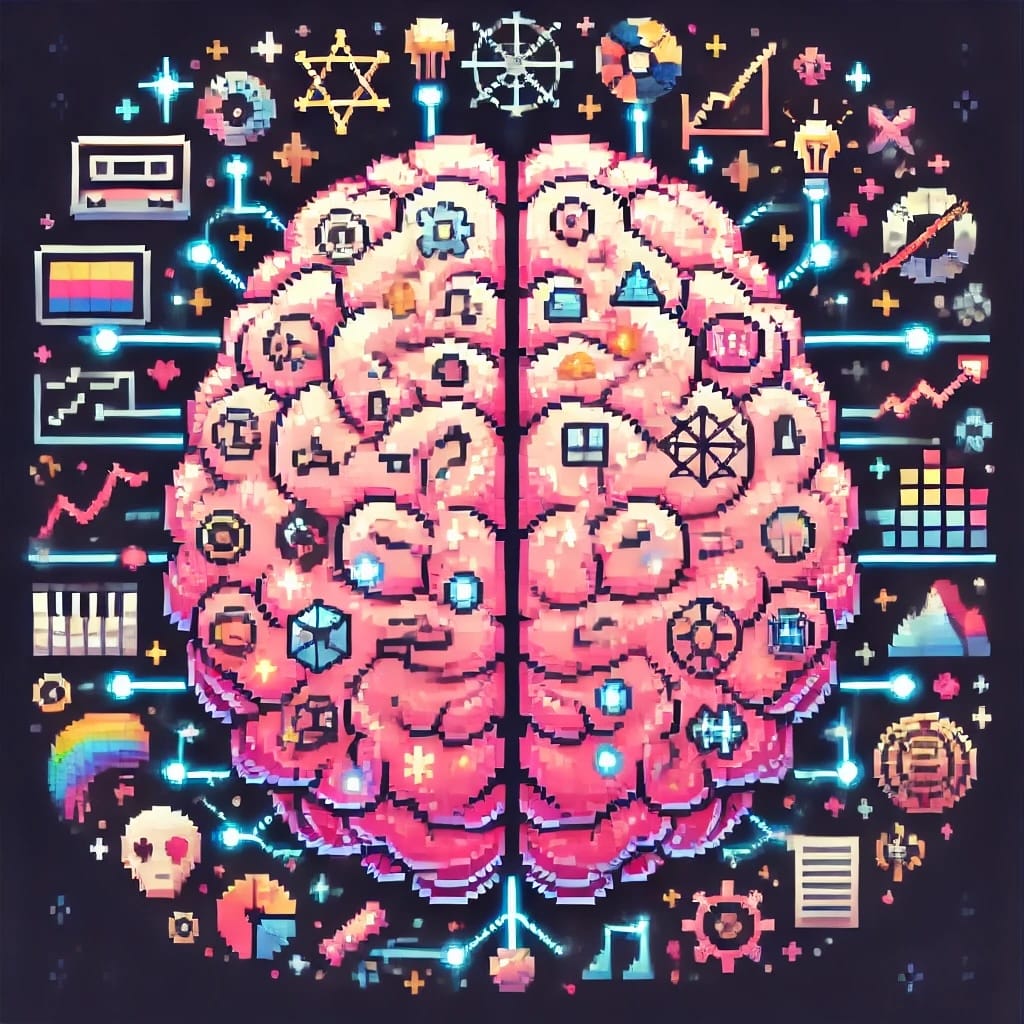

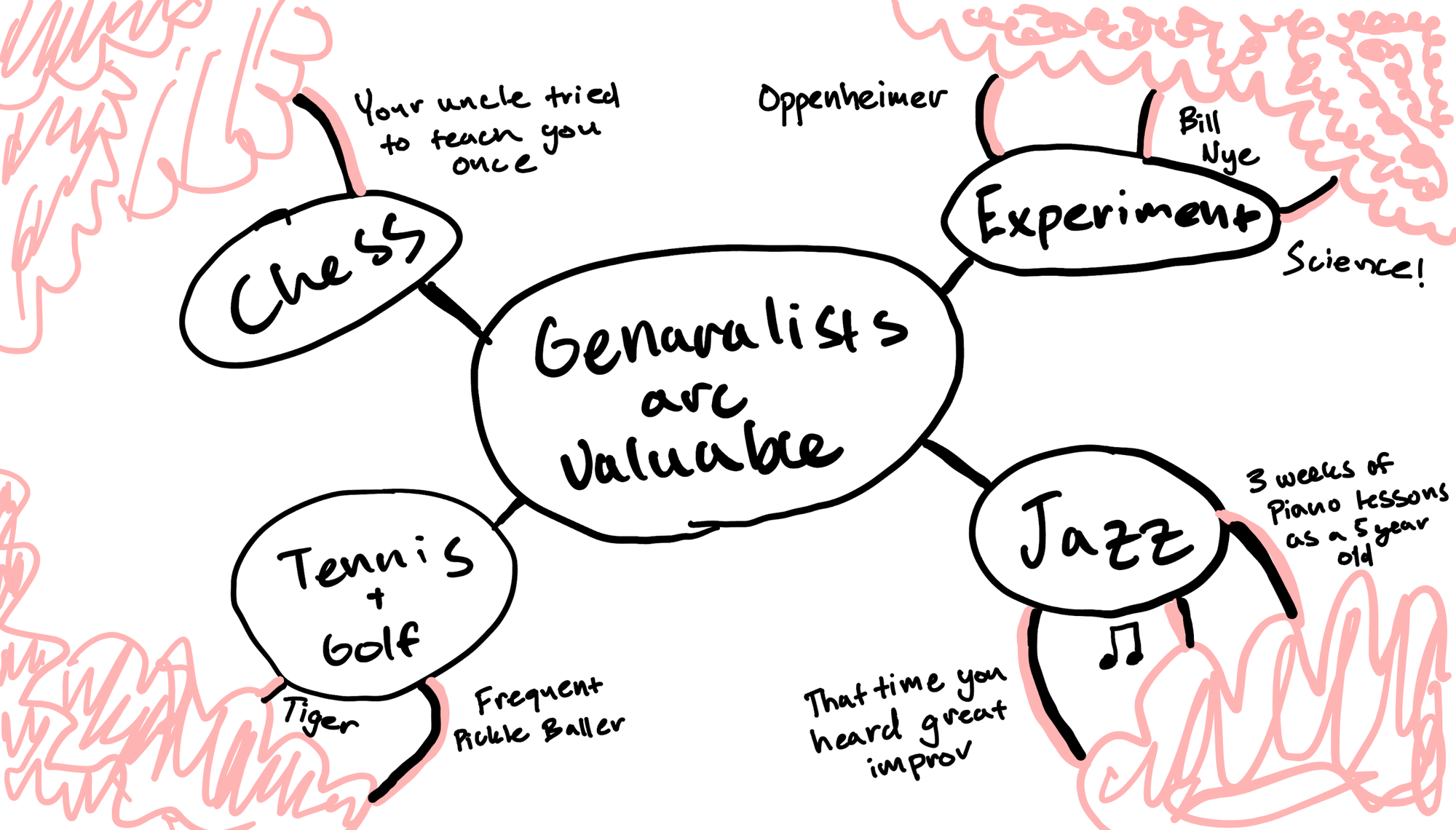

Two weeks ago, in Hidden Complexity, I mentioned how authors sometimes have simple ideas and then fill your mind with examples to help you apply them in the real world. Depending on who you are, these examples may impact you differently and connect more strongly or weakly to a different part of your brain. Using Range as the example, again, I think our brains look vaguely like this:

These examples introduce a lot of nuance to the idea, but many of these things might not make sense to you if you are from a different culture. The more specific the examples, the more they will resonate with a particular group, but the less they will resonate broadly. This implies that the simplest ideas have the potential to resonate with the most people.

The Simplest Ideas

Aphorisms immediately come to mind when thinking about simple ideas that have broad appeal: "If you only have a hammer, everything looks like a nail," "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush," or "It's the journey, not the destination."

Whenever I first heard these phrases as a kid, I understood what they meant on a theoretical level but not in a practical way. They sat there dormant, with the occasional person saying them just enough to keep them in my head.

Then, over years of living, things began to fill in the gaps.

Since these aphorisms aren't loaded with examples, people can interpret what they mean to them and apply them more broadly. The simplicity gives the ideas a sort of evolutionary advantage. The simpler the idea and the more ways it could be interpreted, the more likely it will find new meanings and continue spreading[1].

Some of the greatest wisdom can be captured in simple phrases, but the downside is that when it is simple, it has less immediate meaning to the person it is shared with. The person you wish to give the knowledge may need the requisite (and usually tough) experience of failure and trying to move in a way the world does not work. Some things seemingly have to be relearned every generation... Good novels and biographies where we empathize can help with this process, but that still can’t replace personal experience.

The Bigger Picture

This concept also distinguishes between principles and rules. Principles broadly define what one can and should do but are far less prescriptive than rules. This makes principles easier to teach and replicate across people since they are less nuanced and allow the end-user to adapt them to their specific needs.

There is always a trade-off between being more specific and less specific. The first is hard to pass on but will lead to more predictable outcomes, and the second is more straightforward but could have widely varying outcomes. As with everything, there is a spectrum, and it is important to be thoughtful about the sort of information that you are passing on and the results you want.

If you are teaching someone how to fly a plane, be incredibly specific, but if they ask about how to find a spouse, more general advice that they can adapt to their situation is probably a better solution. You also need to find balance when showing someone a problem you want help with. You likely have a potential solution in mind, so you need to present the issue in a way that opens up their mind instead of narrowing it in around the idea you already have.

Neither complexity nor simplicity is the answer. We always have to be thoughtful about where we land.

- I initially came across the idea for this article when reading The Great Mental Models: Physics, Chemistry, and Biology from Farnam Street. One of the mental models is replication.