On Focus

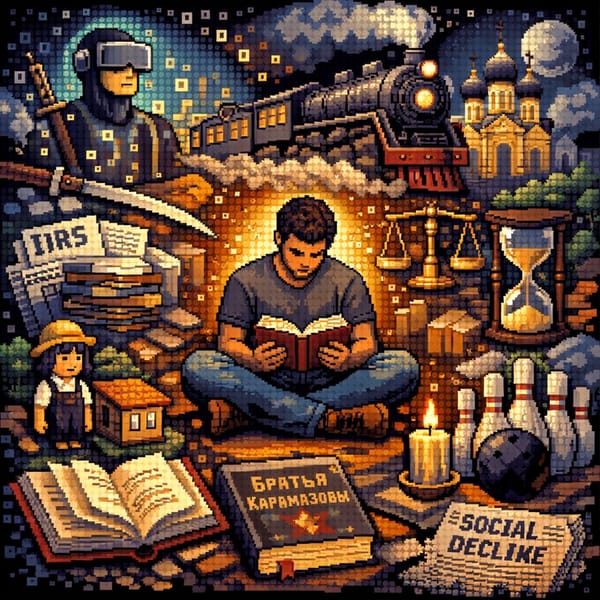

As mentioned in a previous post, I recently went down a focus rabbit hole, reading Stolen Focus and Indistractable and some relevant excerpts from The Shallows and The World Beyond Your Head.

Initially, I thought the narrative would be that we struggle with short-term attention, causing significant productivity decreases. While that is the case, those challenges are well documented so I will focus on what I did not expect to find when I began.

The Medium is the Message

Marshall McLuhan coined "the medium is the message" in his 1962 book Understanding Media. He went as far as to argue that the content didn't matter. The most important thing was how the content was delivered. Without us realizing it, the patterns of the medium change our perceptions of the world.

I disagree that the content doesn't matter, but the medium is more important than I initially thought. This concept relates to what I wrote about in The Great Montage. The use of montages in television shows or highlights on Instagram gives us an unrealistic view of life.

So, what do the various mediums we interact with tell us about the world?

In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari breaks down Twitter's message with a few points. "First: you shouldn't focus on any one thing for long. The world can and should be understood in short, simple statements of 280 characters. Second: the world should be interpreted and confidently understood very quickly. Third: what matters most is whether people immediately agree with and applaud your short, simple, speedy, statements."

Whereas printed books are the opposite. They present life as complex, something you set aside time to think about. You have to slow down and narrow your attention to one thing.

Taking in life as something complex could be why reading novels correlates with greater empathy[1]. I doubt anyone would ever claim that Twitter consumption correlates with empathy.

This prompted reflection on what I am consuming and what that implies about my world beliefs. There is a place for Twitter or reading short articles or newsletters; they create serendipity and can keep you updated on the world, but there is no replacing long-form media for deep understanding.

Mind-Wandering

Letting your mind wander is vital to your brain making new connections. These connections enable us to learn, set goals and long-term plans, and recognize life patterns.

When we overload our brains with stimuli, we cannot form long-term goals or a narrative for our lives. We begin to lose our sense of self because everything we are is external. Johann Hari calls this a "denial-of-service" attack on our brain, a technology-based attack where you make so many requests of service in such a small amount of time that it brings the server down.

Matthew B. Crawford in The World Beyond Your Head says, in some ways, our lack of silence is a tragedy of the commons. He uses the example of an airport lounge where the usual waiting area is overrun with stimuli, and we must pay a fee for silence. People don't reserve the right not to be disturbed. He argues that silence should be treated as necessary for the mind as clean air for the body because if we don't get enough of it, we lose ourselves.

This ties back to what I wrote in Embracing Limits in 2024. My frantic media consumption didn't lead to me learning way more; it led to me being overstimulated and remembering essentially nothing. I didn't need to consume more information. I needed to give my mind more time to make connections with that information.

Memory

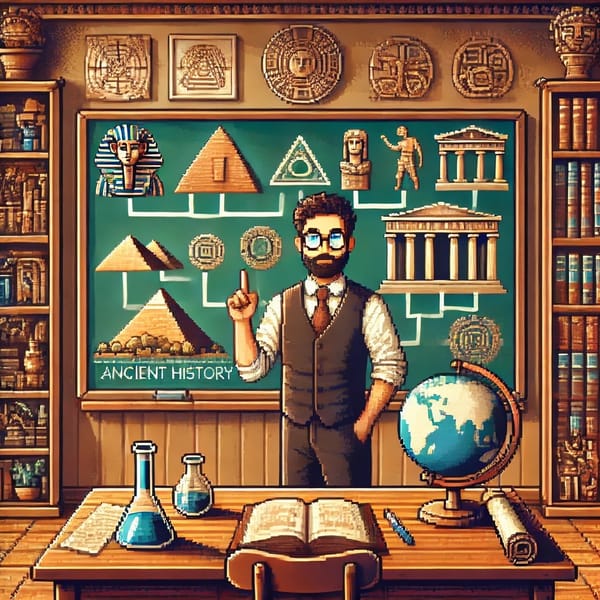

People traditionally see memorization or attempting to memorize something as wrong because our brains are for "having ideas, not for holding them".

I used this phrase frequently for a long time, but I have since realized that having an idea written down or somewhere you can locate it, like with Google, is less powerful than having it readily available in your mind.

Here are a few ways I have found that to be true.

First, it loses context. Cynthia Ozick, a novelist, once said something along the lines of "data is memory without history" (I couldn't find the exact quote). If you don't know why or how it came to be, what you look up has less significance[2]. We are surrounded by information but need more depth to turn it into knowledge.

Second, it prevents you from having the same ideas. Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg compared it to having a flute with a one-second delay between you blowing in and the noise coming out. It limits the types of ideas you could have[3].

Third, learning things changes your brain. The things you learn actively change how your brain functions and how you view yourself as an individual. I suspect this is why catechisms are so widely used. You aren't just memorizing text; you are rewiring your brain.

All these things aren't to say that we should memorize everything, but I am at least trying to remember ideas that I find interesting or surprising more intentionally. I want to keep these things in my head and let them collide with the world over time to see if something thought-provoking may come of it.

Conclusion

Interacting with this technology isn't just changing how we spend our days. It changes our goals, learning ability, and perceptions of the world. The constant stimulation gradually erodes our sense of self.

Underlying all of these things is us losing our individuality. We surrender to the great algorithm in the clouds to tell us where to go next. Technologies pulling at our attention spread us thinner and thinner, weighed down by our abundance of choices.

Appendix (Random Facts + Resources)

- Assuming infinite scroll, the 'feature' that you don't have to click to the next page when you run out of content, increases social media use by 50%. Society collectively scrolls 200,000 lifetimes each day more than they would have otherwise.

- Recommendation algorithms seem to lead to radicalization:

- 64% of Facebook users who joined radical political groups were recommended to join them by Facebook's algorithm.

- It is estimated that if you are watching a historical video about the Holocaust, you are around 5 YouTube recommended videos away from a video denying it ever happened.

- Everyone compares distractability to obesity. The behavior change came from corporations developing something hyper-palatable and freely available. It impacts us negatively as individuals, but it was brought about through environmental changes and will be hard to reverse without some form of regulatory change to align incentives better.

- Correlation is not causation, but they did account for education levels. Here is the full study.

- This is a limiting factor in training AI models right now. Using the internet as training data is excellent, but it doesn't help you learn procedures since all you have is the output.

- I think generative AI will help in some ways, but we assume too much to say that it will look like our brains. Our brains are far more complex than we give them credit for.