The Lesson to Unlearn by Paul Graham (2019) →

Consider Graham’s example below:

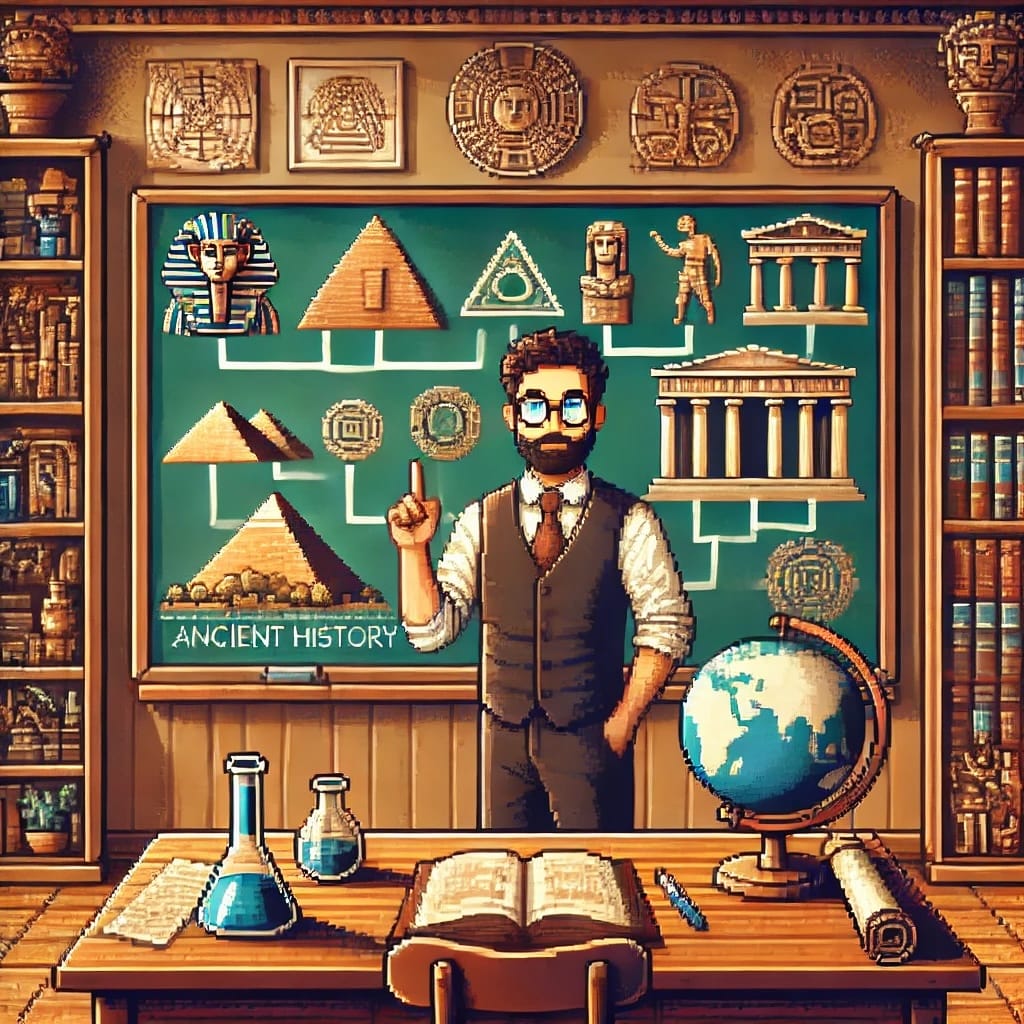

Suppose you're taking a class on medieval history and the final exam is coming up. The final exam is supposed to be a test of your knowledge of medieval history, right? So if you have a couple days between now and the exam, surely the best way to spend the time, if you want to do well on the exam, is to read the best books you can find about medieval history. Then you'll know a lot about it, and do well on the exam.

No, no, no, experienced students are saying to themselves. If you merely read good books on medieval history, most of the stuff you learned wouldn't be on the test. It's not good books you want to read, but the lecture notes and assigned reading in this class. And even most of that you can ignore, because you only have to worry about the sort of thing that could turn up as a test question. You're looking for sharply-defined chunks of information. If one of the assigned readings has an interesting digression on some subtle point, you can safely ignore that, because it's not the sort of thing that could be turned into a test question. But if the professor tells you that there were three underlying causes of the Schism of 1378, or three main consequences of the Black Death, you'd better know them. And whether they were in fact the causes or consequences is beside the point. For the purposes of this class they are.

It makes a strong point that what gets you the A on the test isn’t always (or usually) what means you understand a subject well. Instead, the test simplifies the material through the professor's eyes. When you step out of a classroom, though, reality has infinite complexity, and you can’t take the same shortcut (his word) of having someone else filter it all for you. You focus on what’s required instead of the big picture.

After leaving college, I struggled with this topic. There isn’t always a correct answer or a “way” it should be done. The work needs to get done, and you must figure it out. Think critically and be able to defend why you made your decisions, and you will do just fine. If anything, you will significantly outperform those looking to do what’s required because, like in history class, what’s required is often a considerable oversimplification of reality.